You’ve done it (or you had no choice). You’ve decided to learn another language! But then, quickly, the frustration builds up. Reading and writing is going along ok, but the speaking … the pronunciation. The bane of many language learners: how to actually speak that language without making a complete fool of yourself.

Two quite different problems generally come up:

- which sound to produce

- how to produce it.

In English, for example, there are three ways to pronounce the letters “th” (see How to Pronounce the English “th”).

First, which pronunciation of the three should you use? Second, how do you actually produce the chosen sound?

These are two different issues.

A very useful tool to help solve the first problem is the International Phonetic Alphabet.

(A quick note. Depending on the context, the pronunciation of words is usually written between // or []) but we don’t need to go into that here.

First Problem: Which Sound Should You Choose?

In many languages, choosing which sound to pronounce is not too difficult. Often, you simply pronounce what is written and any letter(s) will always be pronounced the same way. The rule is one (sometimes two or three) letters = one sound. This is the case, more or less, in Spanish, Dutch, German, Arabic, etc. In German, for example, “ü” is pronounced as the French ”u” in bu, vu. In Romanian, “ț” is pronounced /ts/, always. In Spanish “n” is pronounced /n/.

Unfortunately, it is not always that simple. In some languages there is a wide gap between what is written and what is said. This is notoriously the case in English and in French.

In English, as I said, there are three ways to pronounce the letters “th.” There are even more possibilities with the combination “ough” (cough, enough, bought, through).

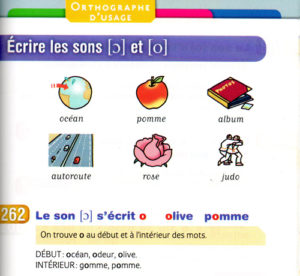

Similarly, it’s not easy if you learn French to figure out that in some cases you pronounce the “e”, as in le, but not in others, as in ville (that’s French for city). The same goes for “n.” You pronounce it in une but not in un. Even worse, in the sentence Cet été, j’irai me promener à pied, (This Summer I will go walking by foot) “é, ai, er, ied” are actually all pronounced the same way: /e/ as in été.

It was in order to solve the problem of which sound to produce that in the 19th century people started developing phonetic alphabets.

The most widely used phonetic alphabet today is the International Phonetic Alphabet.

What is the International Phonetic Alphabet?

The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) was created at the end of the 19th century to help language students and teachers learn the pronunciation of languages. Its inventors were well aware that in some languages the wide difference between spelling and pronunciation was an obstacle to learning languages. Since then, the use of the IPA has spread to almost all existing languages.

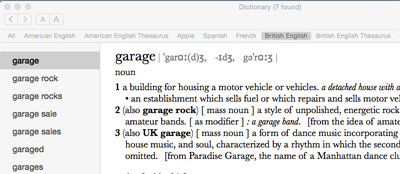

As its name indicates, the IPA is international: it is used worldwide in many printed and online dictionaries, in language textbooks, on web sites, on Wikipedia, Duolingo, in the French-English editing software Antidote, etc. It is one of the first pages in many dictionaries. Moreover, dictionary entries are often followed by their transcription in IPA.

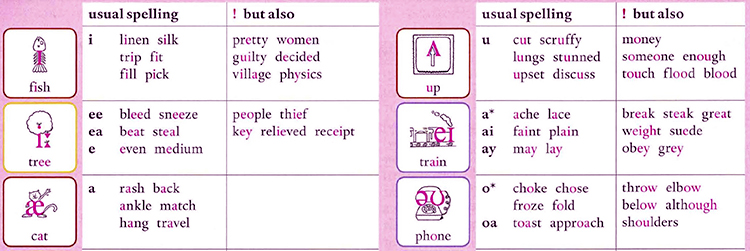

Here are three examples of the use of the IPA: the dictionary on my Mac, wiktionary, and a page in the Bescherelle fondamental, an elementary school language book for French.

The IPA: How Does it Work?

In its basic version, the IPA is a list of signs that indicate sounds. To each sign corresponds one and only one sound, whatever the way this sound is written in various languages. If we take the example in French mentioned above, the spellings “é,” “er” at the end of infinitive verbs, “ai” in some tenses, and “ied” in ”pied” are all indicated by the same sign: /e/.

Other more technical signs exist in the IPA, but these are really only used by linguists and other language specialists.

You do not need to learn all the IPA signs, only those that correspond to sounds used in your language or the language you are learning. For example, the sign /θ/ is used for the “th” in think. Since this sound does not exist in French, or in many other languages for that matter, dictionaries in those languages do not include it in their IPA page. On the other hand, many signs (/b, k, m, p,/ etc.) are common to many languages and have to be learned just once.

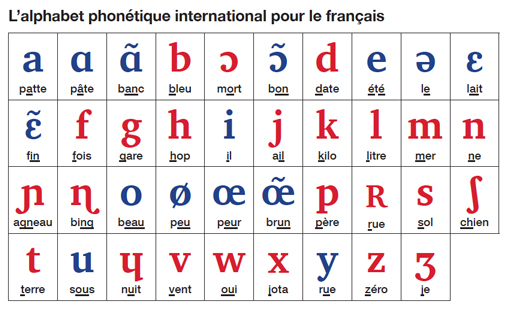

Here is, for example, the IPA signs used for French. If you know these signs, you know which sounds to pronounce for every word in French.

Another example. Here is an interactive presentation of the IPA signs for UK and USA English. From there you can also download an Android or Iphone app to practice the use of the IPA in English.

At first the IPA might seem too difficult, esoteric even. Don’t panic. You get used to it pretty fast. Actually, if you pay attention to the chart, you will notice that you already know quite a lot of its signs.

Here are a few examples to begin with.

Let’s say you are learning French. In the IPA, the sign /y/ corresponds to the sound of the letter “u“ in bu, vu (supposing you know how to say those words). Once you know that /y/ is used for that sound, it is easy to read /by, vy, ty, ny/ (bu, vu, tu, nu) in the IPA, even if you do not know what these words mean.

The sign /u/, on the other hand, is used in French for the sound of “ou” in cou, genou, etc. More or less the same short sound as “oo“ in book (/buk/) in British English.

This is where the IPA is really useful. In IPA /tu/ tells you which sound you are aiming for in tout, toux, tous (when the “s” is muted), all different written words in French but with the same pronunciation.

Another example. The sign /ə/ (called the schwa, the name of a letter in Hebrew) is used for the sound for “e” in the. It is by far the most common vowel sound in English. Once you know that and you look at your app or dictionary, you know that in French you say the “e” in le (/lə/), but not in ville (/vɪl/) since there is no /ə/ in the phonetic spelling. Similarly, if you see “apă” (water) in Romanian and look in a dictionary, you will see /apə/. Since you know the schwa /ə/, you know how to say the word (ă is always /ə/ in Romanian).

Again, this shows the usefulness of the IPA since the schwa sound is used in many languages. I often point out to my students that in about you do not say /a/ but /ə/ in the first syllable. Then I point out to the phonetic spelling /əbaut/ and it really makes a difference. Similarly, it helps learners of English to know that the phonetic spelling for wizard is /wɪzəd/ (or /wɪzərd/ in the USA) and not /wɪzard/.

Why Use the IPA?

The advantage of the IPA is that it is universal, easy to learn and allows you to immediately know which sound you should try to pronounce without having to find a site or a speaker to tell you the pronunciation. You can, of course, learn a language without the IPA, just as you can learn to play music without reading music partitions. The IPA simply makes learning pronunciation easier.

A reminder though. The basic IPA does not tell you how to pronounce a word but which sound to produce. For example, if I see /t/ I know which sound I am targeting not exactly how to place the tongue, which is a bit lower in French and Spanish than in English. For the how, you might still need help, online or in person. It’s nice when you learn French or German to know when you need to say /y/ or /u/, but since many languages do not have the /y/ sound, as is the case in English, Spanish and many Slavic languages, most students still need help producing that sound.

Good online resources

Some interesting reads

- Cahiers de l’Apliut, Phonétique, phonologie et enseignement des langues de spécialité – Volume 1 et volume 2, 2010

- Andy Arleo, Should IUT Students Learn the International Phonetic Alphabet?, 1993

- Dan Frost, La phonétique pour les vaches espagnoles, 2003

- Wander Lowie, De zin en onzin van uitspraakonderwijs, 2004

- Mompean, J. A. (2015). Phonetic notation in foreign language teaching and learning: potential advantages and learners’ views. Research in Language, 13 (3), 292-314.

(The top image is taken from the IPA help sheet in the English File series).